By Scott Eckert and Cecily Lee

Getting acclimated in Quito

We arrived in Quito after a good set of flights, with only a few hiccups. Departure was a tad chaotic because of a huge thunderstorm at our 3:00 am loading time in Elsah. The flight to Miami was smooth, where we had a three hour layover. The four hour packed flight to Quito (they had to remove two passengers to get to legal weight) was also smooth. We got through immigration in about an hour, had food at the airport and arrived at the hotel in Cumbayá (Casa Ilayaku), tired but in good spirits, despite no electricity or hot water.

Ecuador is really struggling with the effects of climate change. Just like the high Arctic, high-altitude areas are more heavily impacted than other areas, with lower snowfall and higher temps shrinking glaciers, more extensive and harsher droughts, and generally more extreme weather.

Ecuador is, in fact, experiencing a drought now. This means a concurrent reduction in hydro-power, the chief source of electric power generation. The government has been forced to put into place rolling blackouts across the country. From the hotel, we saw quite a number of wildfires and got whiffs of smoke.

The next day we took it easy. Cumbayá, the suburb of Quito where we are located, is at about 7,700 feet (Quito itself is at 9,350 ft). We wanted to students to acclimate, so we hiked around a bit, did some bird watching and stayed on their cases to hydrate, hydrate, hydrate. All in all they did well.

The following day we went next door to an animal rehab center where students explored the exhibits and could see what the center does. The most common species they work with are parrots and macaws; there are just too many abandoned or neglected pet-trade birds. They also put on a great raptor show (all in very fast Spanish) complete with black-chested buzzard eagle, Harris hawks, great horned and barn owls.

Orientation at our partner university, USFQ

On Thursday, we headed to Universidad San Francisco de Quito for orientation. Hosting about 8,000 day students, this urban campus is state of the art with incredible modern and well equipped facilities. As a liberal arts university, it’s rare in Latin America, where most higher education is technical. Of the liberal arts schools, it is rated very highly. Ironically it was founded by three Ph.D. physicists (two Americans and an Ecuadorian) in the 1970s, all of whom had a deep respect for broader ways of learning. The second building built on campus is an all-wood pagoda classroom where students take mandatory self-awareness coursework.

Each year USFQ hosts more than 1,000 international students, many of whom come on their own for a full semester. We’re relatively unique in that Principia abroads are multidisciplary and emphasize cultural competence and personal character development along with academic content. Hence we provide the faculty who teach while the group is traveling, as well as a resident counselor. USFQ is a fantastic partner, handling logistics very effectively and offering great learning opportunities, such as the specially arranged three week block of Spanish at two levels, taught by Ecuadorian teachers,specifically for our students. After the morning tour of the campus, we had to forego the scheduled afternoon tour of the older part of Quito due to fires along the main road and smoke in the city. The government had asked all folks to limit travel to ease access for fire fighters and emergency personnel

First high-altitude experience

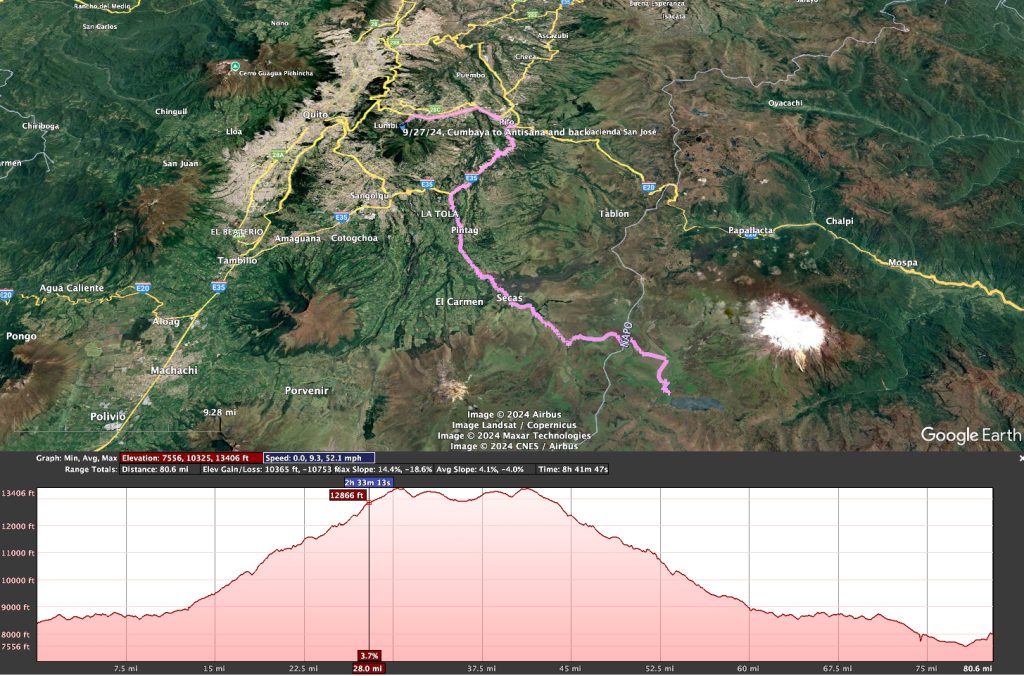

On Friday, we took the students on an all-day excursion to Antisana National Park. This was their first foray to high altitude at just under 14,000 feet in the “Sierra”, the local term for the Andes mountains. The above tree line ecosystem there is called the “Páramo” — all bunch grasses and cushion plants which have evolved for the harsh conditions of widely fluctuating temperatures, high winds and intense radiation. The students ran bird surveys in teams and measured solar irradiation at this high altitude. We also spent some time reviewing plant morphological adaptations under these conditions. Got to see lots of cool critters like Carunculated Caracaras, Stout-billed Cinclodes, Harris Hawks, and an Andean Fox.

On the way back down, we saw two Andean Bears (formerly called spectacled bears) feeding on bromeliads across the river, a few hummingbird species, including the world’s largest — the northern giant hummingbird — as well as an Andean Condor. The trip to Antisana was a good test trip to the Paramo and high altitude, as we prepared to travel to Chimborazo. The students also had a good chance to see how folks live in the Andes as we travelled through towns and villages.

Experts on indigenous peoples

On Saturday, two USFQ Professors — one an anthropologist and the other an archeologist – lectured the students on the indigenous peoples of Ecuador. It was fantastic to hear the complementary perspectives of the two disciplines. From the anthropologist, we got a good sense of the social structure of the various peoples and the more recent organization of modern indigenous people’s social movements, including efforts to maintain their cultures and defend land and resources rights. From the archeologist we got a more complete picture of the history and geographic distribution of human settlement in the region, as well as some of the common themes in religion, art etc. She took us to the USFQ archeological repositories, where students got to examine all sorts of remarkable artifacts from pottery to bone carvings.

At 16,500 ft+ on Mt. Chimborazo

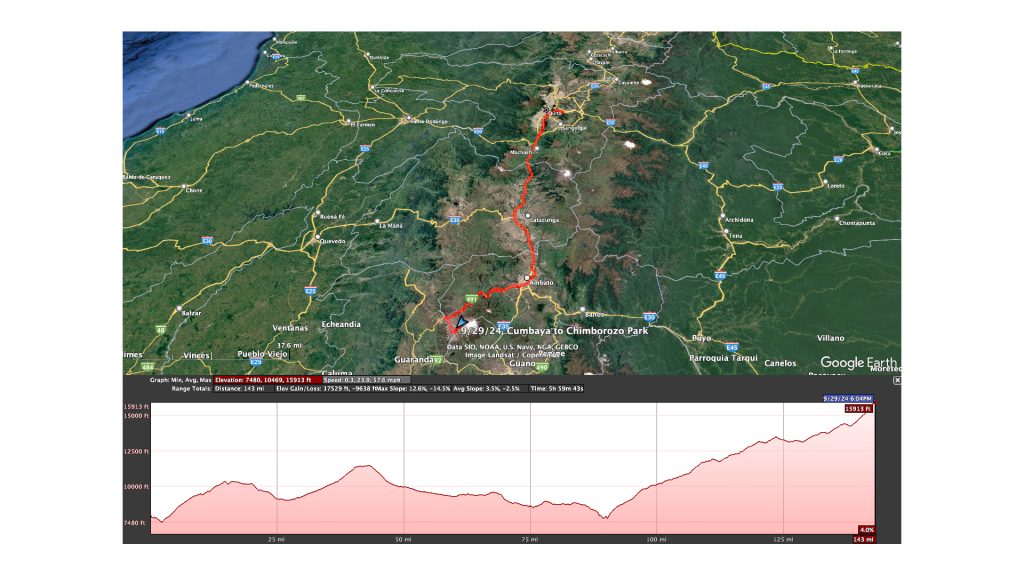

Sunday was the big day! We were headed to Chimborazo — the highest mountain in South America and the closest point to the sun on earth. It was a long bus ride, around six hours, but on the way, we ran into a wonderful parade in a small town! All the local towns were represented, and the variety of clothing worn was an incredible illustration of Andean diversity.

At 20,550 feet, Mt. Chimborazo is about 8,500 feet less tall than Everest, but because it’s on the Equator, it’s around 6,000 ft closer to the sun. It’s right up there with the world’s tallest mountains. Our goal was to stay at the Chimborazo lodge at 13,123ft (close to the elevation of Mt. Rainier). This iconic lodge was established by a famous Ecuadorian mountaineer — Marco Cruz. He’s climbed all over the world for more than 50 years with all of the world’s greatest mountaineers. His lodge uses a remarkable collection of climbing gear from the past (some of which Scott has used!) for décor, giving it a very alpine feel.

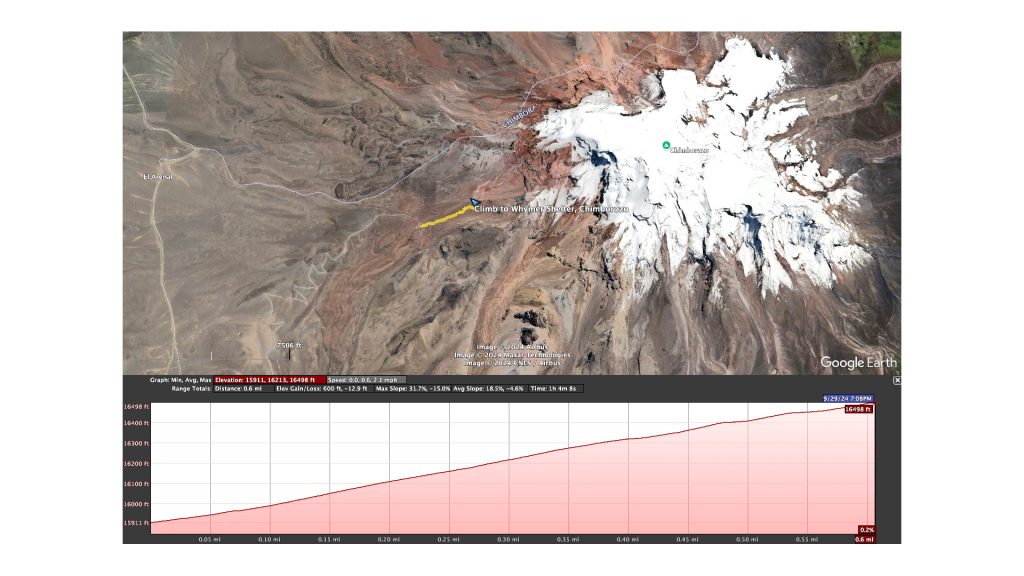

However, before going to the lodge, we wanted the students to have yet more acclimation and experience the ecosystem. So, we took them into the park and climbed up the mountain to Whymper Refuge Shelter at 16,542 ft! The climb from the main lodge to the refuge was about 600 foot elevation change on a very steep trail and was quite the challenge, all in a light snowstorm! Some of the students just charged up there – well, not exactly charged, but rather, using a mountaineering ascent step pattern, they steadily and slowly plodded their way up. For Scott and a few others, it was count 50 – 75 steps, pant for 5 minutes, then 50-75 more and so on. I believe we all made it!

As we approached the refuge hut, we saw some of the longer hair of our students beginning to float. (When air becomes electrically charged and hair stands up, the potential for lightning is very high). Since we’d been hearing thunder, we took the precaution of hunkering down in the hut until the potential for lightning was gone and then headed back down. At this height, there was virtually nothing living except lichens and a few hardy mosses. Our journey to the lodge, down a winding two lane road in a big bus, was almost as thrilling as the climb.

The Chimborozo lodge was quite comfortable, with all of us bunking two to a room. Chris and Scott shared a room with a remarkable decor of climbing memorabilia. The lodge was named for famous climber Reinhold Messener, who had climbed Chimboroza with Marco Cruz in 1992.

Cruz has climbed Chimborozo more than 1,000 times! Their room was dedicated to Lional Terray, a famous French climber from the 50’s and 60’s and other’s rooms were dedicated to other climbers.

High altitude animal species and indigenous communities

Marco maintains a nice herd of Alpaca (and one Vicunha) that are used for their wool. He strongly protects the ecosystem around his lodge. There is an endemic species of hummingbird (Andean Hillstar) using the eaves to nest, Harris hawks, short eared owls nesting in the cliffs, and Andean rabbits galore!

We used the lodge as a base of operations for visiting two Andean villages, one at La Moya, and one at Salasaca. On our return from one village, we had the pleasure of getting to know Marco, who had driven up from his home in Riobamba. What an incredible person! He and Scott spent an hour wandering his property, talking about the ecosystem.

La Moya community

Our visit to the village of La Moya was exceptional. This Andean village of about 300 people is at around 11,000 feet. Three wonderful women of the village showed us around, talked about their lives, food, making of alpaca wool textiles, and medicinal plants. Escorting them was one of the women’s alpacas named Benjamin. While demonstrating the crocheting and making of thread, one woman exploded with joy when student Anna Dilley hauled out her own knitting to show them what she was making.

After a good hike into the hills (more huffing and puffing) to see medicinal plants, we had lunch prepared by the village, then headed back to the lodge for a wonderful dinner. Everyone was pretty tired so sleep that night (despite the altitude) was good for most. A few students struggled a bit, but we got them through it.

Village of Salasaca

The village of Salasaca was our destination the next day. There villagers showed the students how they weave on their looms and how they make flatbread, providing a very nice local meal. This included a taste of guinea pig (called “cui”), a special meal in the Andes, quite chewy. We also took a hike to better view the valley the village is in and to hear local lore, as well as get instruction on medicinal plants. The visit culminated in a ceremonial dance, explained in terms of celebrating the fertility of the land.

Baltazar, the ice man

Our return to Chimborozo lodge still had the mountain shrouded in clouds but it was early enough to explore the property in daylight. It’s quite an amazing location. At dawn the mountain finally revealed itself! It was wonderful to see such a majestic sight after days of viewing only the base! After a quick pack and breakfast, our bus arrived and we headed around the other side of the Chimborazo National Park to another hotel (thankfully at a lower elevation around 9,000 feet). There we visited Ecuador’s highest train station, now closed due to cancellation of their train system (as well as their post office) for financial reasons.

Our main reason for being there was to meet a famous indigenous Ecuadorian named Baltazar, known as the last ice man. He practiced the business of harvesting glacial ice from Chimborazo by hand. It’s brutally hard work to take a burro up to one of the glaciers, carve off two 40 lb blocks, wrap them in grass for insulation and carry them to market (for 4 dollars a block!).

With the glaciers receding, Baltazar was the last one to maintain this traditional job and he became something of a celebrity and national treasure. (You can find a number of these videos on Youtube.) The students really enjoyed the visit and got another insight into being an Andean in Ecuador. Sadly, Baltazar passed on very shortly thereafter. We’re super grateful the students were able to meet him and hear his stories.

Andean vegetable market and art workshop

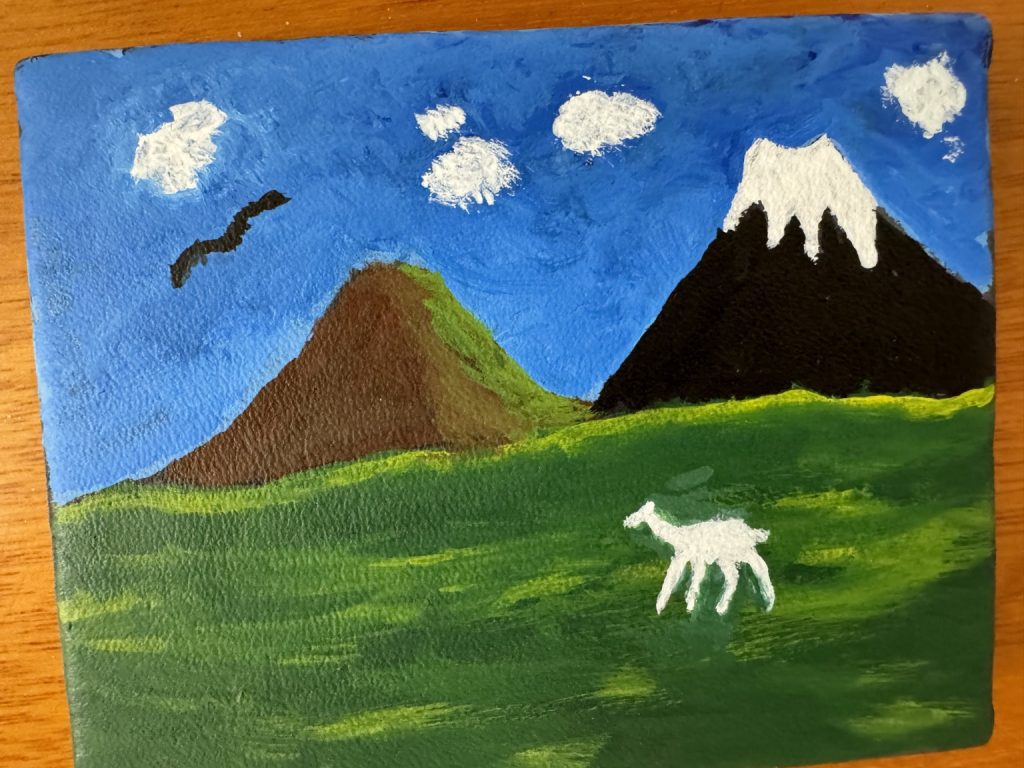

The next day we visited a fruit and vegetable market — a fantastic experience. The students explored for a couple or hours, talked to the vendors, tasted everything and really got a feel for the foods of the Andes. Then our wonderful guide, Alejandra, set us up to visit an indigenous (Tigua) art workshop, where the artists practice a unique form of painting on animal (sheep) skins. Originally done as a means to decorate and tell stories on their drumheads, it has evolved into a wonderful art form using traditional themes.

They even gave everyone a small canvas and walked us through the making our own paintings of traditional subjects (mountains, condors, llamas, clouds). This gave us a much better understanding of how difficult this art form really is.

Back to Quito for homestays and Spanish classes

It was good to get back “home” to Casa Ilayaku in Quito, get our laundry done (a major challenge with the power blackouts) and repack. The following day was another big one — the first morning of Spanish classes, followed by afternoon pickup up of students by their homestay families. Lots of nervous faces as, pair by pair, they left with the family with whom they were to spend three weeks!

Meanwhile, Cecily, Tracy and Scott headed for our Airbnb, as Chris headed to the airport to fly home. The drought seemed to have broken — heavy rains nearly every afternoon, but unfortunately, this did not last. Consequently, the rolling blackouts continue and will probably do so until the water reservoirs are refilled. What this means is that power is off around 8 hours per day, usually scheduled in two blocks with the schedule varying by neighborhood each week. Good thing headlamps are on the packing list!! Lack of power also means lack of internet and sometimes uneven cell phone service. Plus sleep interruptions as generators start up and alarms go off in the middle of the night. Restaurants and small businesses have to close or operate by candlelight.

After one needed adjustment, all the students are really enjoying their host families. This immersion into the language and culture is a plunge that takes courage but is also invigorating! The students also report that they’re enjoying their three-hour Spanish classes with teachers Gissela and Paúl, and their progress is readily apparent! We go to campus each morning to check in with the students as they arrive by bus, taxi or Uber. We then work on campus and meet with them in the early afternoon as needed.

Interviewing experts

As part of the cultural studies course, each student has chosen a topic of interest and is interviewing three individuals on it, to the degree possible in Spanish — some English is allowed! A number of them have chosen topics related to their majors and future careers. USFQ has helped us identify professors with relevant areas of expertise with whom they can converse. The intent is to have the students see themselves as capable of working professionally in an international context. Presentation of their findings is happening at the end of the Quito segment.

A day of service

Developing a sense of service to mankind is inherent to a Principia education. We had the chance to put that concept into practice one day when classes at USFQ were cancelled for a holiday. We spent the morning volunteering at a Quito shelter called San Juan de Dios, which serves over 500,000 people a year. We were divided into three groups – one folding mountains of clean laundry, one making beds, and one helping cut fresh cantaloupe for the lunch that day that would be eaten by some 250 people. On our tour of the facilities, we also visited with elders who live there permanently, and with some children, including three sisters recently arrived from Venezuela. It was a rewarding sharing and caring experience! In another service opportunity, our two most advanced Spanish speakers volunteered four mornings at a city school, where they helped teach English and other subjects.

Group outings

Some afternoons we go on excursions. The destinations have been: 1) the city’s historic and political center; 2) a chocolate tasting and lecture on cacao by USFQ’s director of nutrition — at Paccari, an environmentally and socially responsible Ecuadorian chocolate manufacturer; 3) the province of Imbabura, where we saw the sacred landscape of the crater lake Cuicocha and visited the famed

Cuicocha and the famed Otavalo indigenous artisans market; and 4) the Chapel of Man, featuring the paintings of Oswaldo Guayasamín, Ecuador’s best known artist, and his unique pre-Columbian and colonial art collection housed in his former home.

And now we prepare to go to the Tiputini research station in the Amazon… stay tuned!