As a department, the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) is reading How Learning Works: 7 Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. For our first assignment, we are focusing on the first chapter of the book, called “How Does Students’ Prior Knowledge Affect Their Learning?” Before I read this chapter, I’d always been a supporter of activing prior knowledge and thought that it was the best thing ever, no matter what prior knowledge I activated or engaged in the students. Activities that I’ve used to activate this prior knowledge, include gallery walks and Know-Want to know-Learn (KWL) charts. When I first did these activities, I could tell my students were completely overwhelmed with the information I was providing for them. I could also tell that they were not sure what was most important for them to read or see. As I got this feedback from them, I realized that I need to rein in how I was having my students activate prior knowledge with these activities.

What I learned from my experiences was further solidified in the first chapter of CTL’s assigned reading. As I read the chapter, I saw that it was extremely important to be aware of the prior knowledge I was providing for my students. I realized that I was not guiding my students enough towards what prior knowledge I wanted them to activate, know, or learn. In chapter 1, the authors tell us that there is much more to activating prior knowledge. They discuss ways that I can activate prior knowledge, engage prior knowledge, and gauge prior knowledge. I really appreciate how the chapter laid out the positives and negatives of activating prior knowledge. In fact, it had not really occurred to me that there would be inaccuracies with activating prior knowledge. This new perspective made me realize how important it is to capitalize on what the students do or do not know. If I properly active prior knowledge, then I will only be building on a strong foundation. To do this, I’m going to share a few of the strategies that I read in chapter 1 to learn students’ prior knowledge. These strategies are:

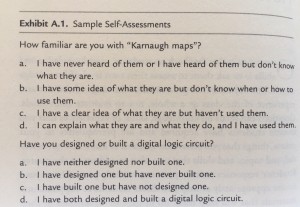

- Have Students Assess Their Own Prior Knowledge

To do this, “Ask students to assess their level of competence for each concept or skill, using a scale that ranges from cursory familiarity (‘I have heard of the term’) to factual knowledge (‘I could define it’) to conceptual knowledge (‘I could explain it to someone else’) to application (‘I could use it to solve problems’)” (p. 29). See the pictures below some examples from the book.

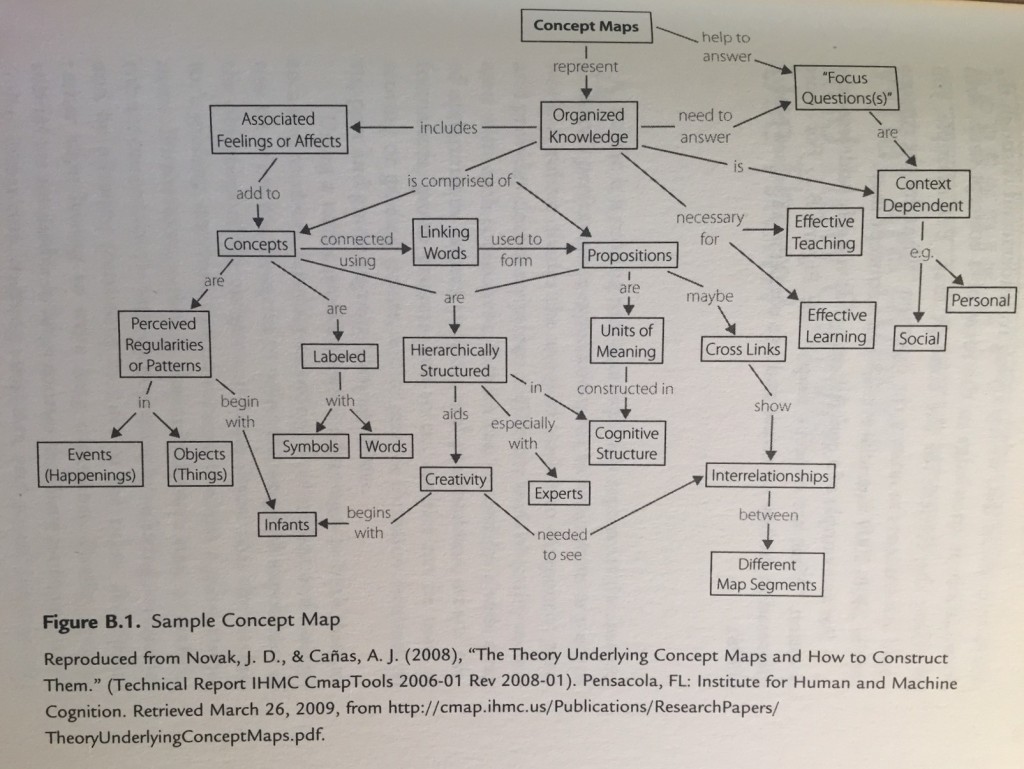

- Assign a Concept Map Activity

The purpose of a concept map activity is “to gain insights into what your students know about a given subject…representing everything that they know about the topic” (p. 30). The concept maps helps the students visually represent what they already know. For an example, see the image below.

These are just a few of the strategies that Amborse, Bridges, Dipietro, Lovett, and Norman share in their book. I am excited to implement these strategies. If you get a chance, make sure to check out the book! For more information, see the citation below. Happy teaching!

Ambrose, S.A., Bridges, M.W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M.C., and Norman, M.K. (2010). How Learning Works: 7 Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.