by Mildred Cawlfield

As the Acorn two-year-olds were departing after a morning school experience, some carried remaining treats of fruit pieces in cups. Eric leaned over and peered into his twin brother’s cup.

“All gone,” said Tom, holding his cup up for his brother to see.

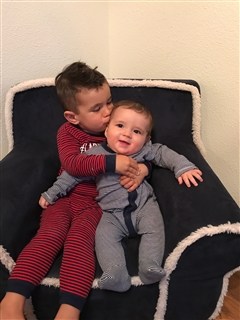

Spontaneously Eric reached into his own cup, took out some pieces, and put them into his brother’s. Both grinned as they walked out munching their treats. This natural brotherly affection can be the norm when we reject the belief that siblings must be rivals. Despite that widely accepted, self-fulfilling belief, brothers and sisters can be the best of friends.

Before the birth of our second child, I had been convinced of the inevitability of sibling jealousy, so I expected it and prepared for it. After the younger son came, I at first consciously withheld affection from him in the presence of the older son because of this expectation. And, of course, I saw the jealousy I was looking for.

Fortunately, since love, peace, and harmony were valued in our home, the sense of rivalry was overcome and the boys became close friends.

Several years later, with two more children, we had an opportunity to replay the opening scenes of the sibling drama. This time I saw that the affection I expressed for the little one in the presence of the older child became a model for him. Obviously, the baby was a new family member to be cherished and our older child fulfilled our expectations as a loving brother.

Adjusting to a new family member is a learning experience for an older child, as well as for the parents. You can prepare the older child by talking about friends of his who have a baby brother or sister, and tell him, “Now it’s time for us to have a larger family.” You can help the child see that it will be a promotion, to be a big brother or sister – one which will include some special privileges, too, like being able to help push the stroller or stay up an extra half-hour.

If there is too much talk about the baby months before its appearance, however, the wait can seem interminable to a two or three-year old, so save most of it for the month or two before baby’s arrival.

Make any changes, such as moving the older child to a big bed, well in advance of the birth. Explain (in this case) that he is now big enough for a big bed, rather than that the crib is needed for the baby.

After the baby comes, show the older child pictures of himself as a baby. Tell him how he used to wear diapers but now he can use the toilet and gets to wear big-boy pants. Tell him that he couldn’t talk to you then and tell you what he wanted, as he can now, and that he just cried when he needed something – that when he was a baby he had to stay wherever you put him, so you tried to find happy places for him to be, but now he can walk and run wherever he wants to go. Let him know that you took care of him just as you now care for the baby and that the baby will grow like he is and will later be able to play with him.

Be sure to point out that baby’s admiration for his big brother or sister when the infant is watching. For instance, “See her watch you. She thinks it’s great the way you can run and walk and eat all by yourself.”

An older child has an opportunity to learn selflessness and patience while he waits for baby’s needs to be met. He also should know that the baby himself will learn patience. At a time when nothing more needs to be done for the baby, you can say, so that big brother can hear, “Baby, you’ll have to be patient now. Johnny needs me.”

Your older child can learn to be gentle with the baby. Talk to him about using his gentle hands; tell him that he is strong and mustn’t use all his strength when he hugs baby, just as Daddy doesn’t use all of his strength when he hugs. Gentleness is holding strength in reserve.

When children are close in age, it’s best not to establish ownership of all toys or to try to have two of everything. Each child may have a few very special things of his own, like a favorite stuffed toy or something for which he has a unique interest or attachment. These should be put in a certain place out of the way.

An older child may want to work, at times, at a table out of reach of a younger one, or may want to have a gate across his door while he builds with blocks and construction toys. Toys inappropriate for a younger one, such as crayons, paints, or those with small pieces, should be kept out of his reach and played with during his nap time or in a closed-off area.

Most toys should be jointly owned and used on a first-come/first-play basis. This eliminates much needless ownership hassle. If a child is playing with a toy and the other wants it, the latecomer can learn to say, “May I play with it when you’re through, please?” Then he can play with something else while he awaits his turn. If these policies are established early, the children will learn to co-operate in the same way with other playmates.

When there are disputes, it’s best for parents not to take on the role of judge and assess blame, though they can make it clear that the problem must be solved in a peaceful way. “We use words, not fists,” is one good rule. The children themselves can be made to sit and talk over their problem until they come up with a solution. At first you may need to help by asking each one to tell the other how he feels or by trying yourselves to verbalize their feelings for the children.

For instance: “Heather feels that you don’t love her when you push her, so she cries” or, “Tony didn’t understand that you were playing with that truck, and had just parked it while you were looking for a man to put in it.” This kind of help not only shifts the responsibility for solving social problems to the children but gives them the means for finding solutions. If one child is clearly the aggressor, however, the parent might have him sit by himself for a few minutes to think about how he can use his loving hands or feet.

I recently asked a mother of four children close in age what ideas had been most useful to her in encouraging sibling friendship. She said that it’s helpful for the children to work together toward a common goal, so she looks for goals such as cleaning up for outside time, planning a party, or deciding what to have for dinner. Each child takes a part in accomplishing the main goal and appreciates the contributions of the others.

When the children have a spat, this mother has them sit and talk it over until they can come to her with their solution. She has found that ridicule and rivalry can be eliminated – when a child is feeling fear or inadequacy – by encouraging another to help him. For instance, one of her younger children was afraid of the dark and an older one, who had overcome that fear, was asked to talk to her and help her. This family has discovered that one never wants to put down a friend he’s helping.

Children don’t really want to feel equal to each other in every way. But they do – each one – want to feel special and appreciated. As parents, you can do much, both to help your children appreciate each other’s uniqueness, and to set the stage for harmony. On top of everything else, working toward the goal of peace at home is bound to add needed peace to the world scene.

*names have been changed