Written by Mildred Cawlfield, Winter 1977

Sally spontaneously shares her candy with Jill. Jeff runs over to help little Billy, who just fell of his tricycle. Keith and Kevin work out their disagreement with words instead of fists. This is the harmony between children we’re working for, and there are many things we, as parents, can do to promote it.

Sandy, our toddler, sees another child playing with a toy. The toy takes on new life. Barely conscious of the other child, Sandy walks toward the toy and grabs it. What does she need to learn? That people are not toys; they have feelings, and she can affect those feelings. But if we, the adults, grab the toy from her in turn, with a spank and reprimand, to return it to Joey, Sandy—despite our disapproval—is learning that grabbing and hitting are effective methods. We really do teach more by our actions than by our words.

Suppose we say, “Joey feels sad when you take his toy away. Let’s give it back, and he’ll feel happy again.” As we say it, we hold our toddler’s hands and help her return the toy. We can say then, “Oh, see how much better he feels!” Then to Joey, “Sandy would like a turn with the toy when you’re through. May she please play with it when you’re finished?” Next, take Sandy away from the scene and help her find a good alternative toy to play with—perhaps even play with her for a moment. When Joey loses interest in the coveted toy, he can be helped to share it. “It looks like you’re ready to play with something else now, Joey. How happy Sandy will be when you share this toy with her!”

Describing feelings helps a child become aware of them, and this kind of intervention teaches empathy, a necessary ingredient to the expression of love.

Studies show that there is a correlation between harsh physical punishment and aggressive behavior in children. Also, it has been found that ignoring aggression that takes place in an adult’s presence perpetuates it, because the child feels that the aggression is being condoned. So it’s important to take consistent, appropriate action. This does take our time, and it may seem easier to let the children fight it out. But what rewards there are for spending the time now to teach these needed skills! We not only gain a more harmonious home but build skills desperately needed in the world.

A good rule for children—like Sandy and Joey—to learn is that we shouldn’t take anything from another person by force, no matter how much we want it. We can ask if we may please have a turn with it when they’re finished. Then children can learn that it helps to get busy with something else, because standing around eagerly awaiting something seems to cause the possessor to maintain his interest in it.

We don’t teach sharing by making a child give something he is working with to another. We’re merely fostering possessiveness and resentment. If an adult is reading a magazine and is in the middle of an interesting article, we wouldn’t expect him to give it up immediately just because someone comes along and says he wants it. Yet we sometimes make that kind of demand on a child. Sharing comes from the desire to give. It is the feeling we want to foster, not just the act.

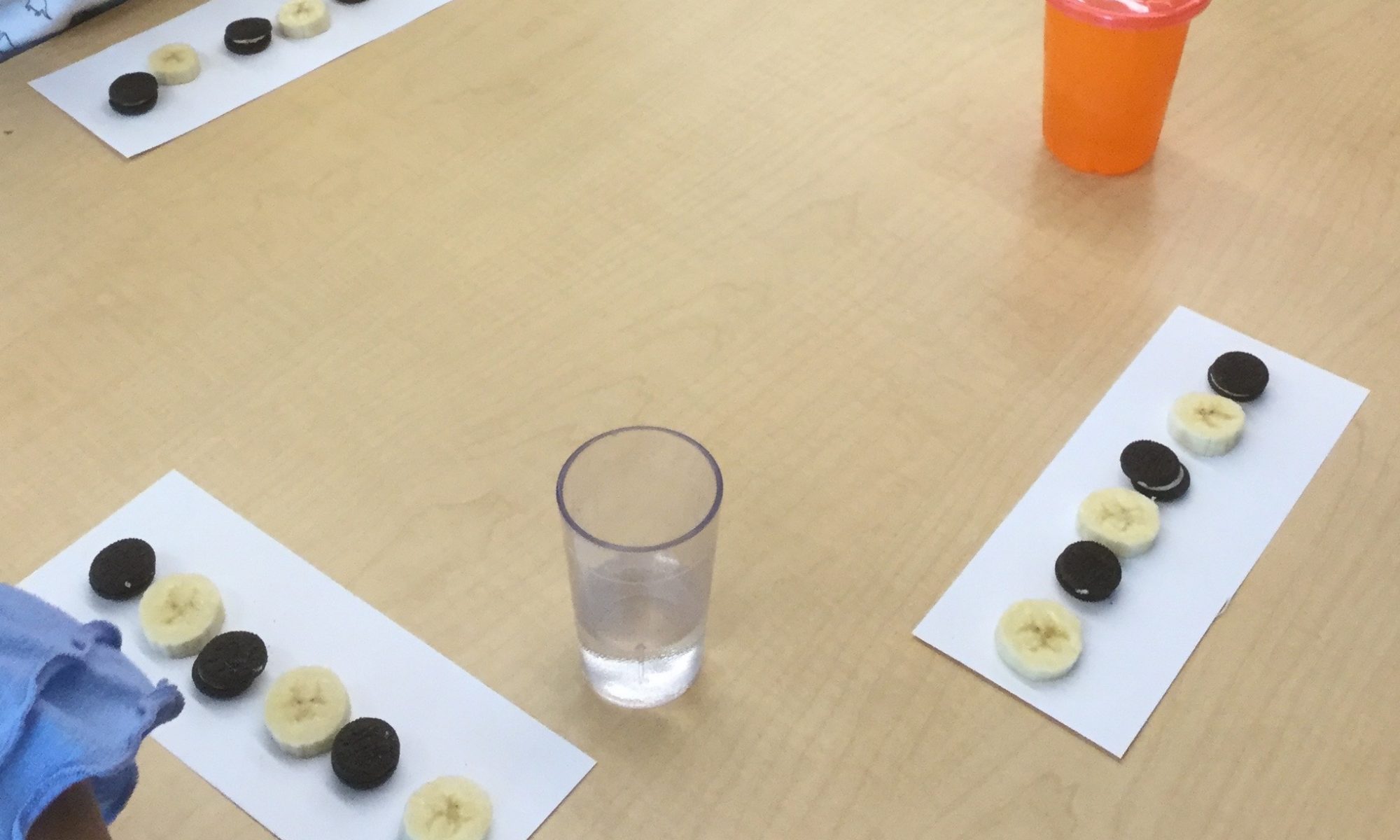

Food is a good thing to use for practice sharing. A child enjoys the obvious pleasure he gives others by passing out cookies or candy, and we can point out, “It makes your friends happy when you share with them.”

Taking turns is another social skill children must learn. We can take turns speaking at the dinner table, and children can take turns being pushed in a swing or riding a wheel toy. Turns can be measured by counting. We can show what fun it is to take turns and should bill it as a positive, rather than a negative, experience.

When children disagree, they need to learn to settle their differences verbally rather than physically. “Use words, not fists. Talk it over,” we can say. Sometimes it helps to verbalize a child’s feelings and thoughts, such as “Tommy thought it was fun dancing in a circle with you, but when you went too fast, it frightened him,” or “Johnny would like to have a turn being the daddy instead of always the child.”

If one child continues to act aggressively toward another child and doesn’t respond to another’s viewpoint, he needs to learn that Principle operates to protect. We need to firmly, though lovingly, take him from the scene to sit on a chair until he can use his good thinking. We can tell him that thinking governs actions, and when he uses good thoughts, he’ll have good action. We can also tell him that we can’t let him hurt another, just as we wouldn’t let anyone hurt him.

It helps children relate to others when we point out how we and others are similar to them. “Jody likes dolls just as you do.” Or “That loud thunder startled me, too. Aren’t we glad God is here taking care of us?” This type of relating helps children understand the concept that we are all God’s children and forms the basis for practicing the greatest social rule of all, the Golden Rule.