Written by Mildred E. Cawlfield

A group of Acorn parents, in discussing their concepts of education, used these words and phrases: unfolding; developing; uncovering; discovering; recognizing what’s there and providing opportunities for its expression; stating goals; establishing a foundation that integrates the spiritual, moral, intellectual, social, and physical; learning to look away from self; putting off ignorance and limitation. They decided that education is not adding something to the child, nor writing on a blank slate, nor waiting for a child to go through pre-programmed stages.

One parent remarked that it is not so much like stuffing sausage into a casing as it is opening the oyster to find what’s there.

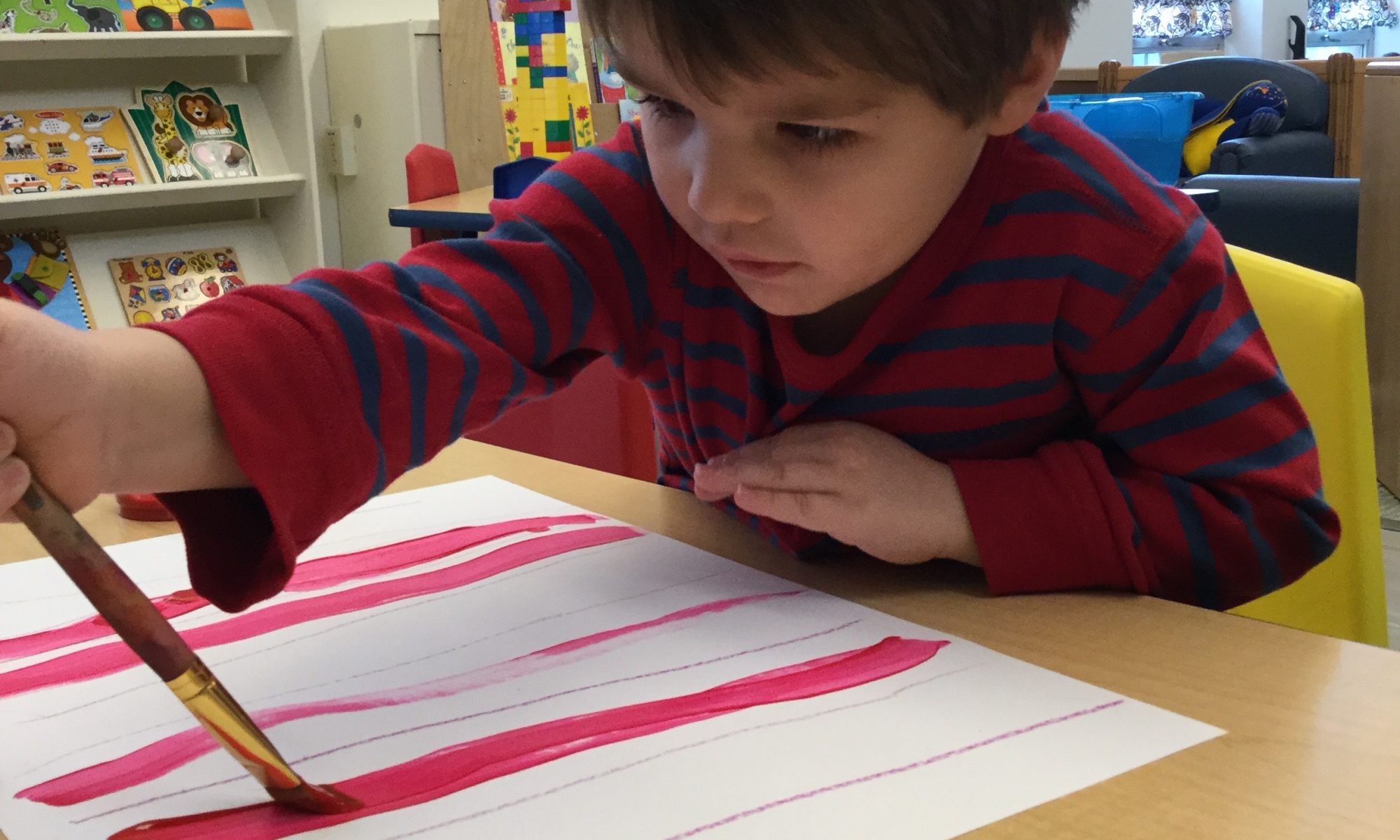

What teaching methods, then, follow from this concept of education? If our goal is not merely to fill children’s minds with knowledge, we’ll look for methods which bring forth and reveal their limitless capabilities.

The most powerful teaching method is the teacher’s recognition and acknowledgement of the child’s present intelligence, memory, discernment, strength, balance, grace, selflessness, etc. This awareness leads the child to see in himself, and to express these qualities.

Suppose a child is behaving aggressively toward other children. If our first step is to see him as an expression of Love, we will be ready to say to him, “Show him your gentle hands. Hands are for loving and helping.” We can then show him how happy his loving hands make his friends feel.

Perhaps he needs to acquire the ability to use verbal language. We will see him as the expression of all-hearing and all-knowing Mind and will continue speaking to him even before we get a verbal response.

A number of studies in education have shown the value of expectancy on the part of the teacher. Teachers in one study were told that certain students were very bright and could be expected to show great gains. Though these children were chosen at random (unknown to the teacher), they did show much greater progress than other children in the class. This illustrates how helpful it can be to see and expect evidence of the great capacity for learning in each child.

Another important teaching method is to show by example – that is, to model. Children’s quickness at picking up good ideas they see demonstrated shows the “do as I say, not as I do” approach as ineffective. Not only are parents and teachers constantly teaching language, customs, and courtesy by their actions, but children are learning much from each other. When they see other children being obedient, cooperating and sharing with each other, they are quick to follow suit.

Parents and teachers encourage this type of learning when working with more than one child by noticing those who are doing the correct thing – i.e., “Amy’s helping me put toys away. Thank you, Amy” – or, “I like the way you remembered to say ‘Thank you’, Johnny. You’re welcome!” Also, one teacher or parent can remark to another, “Did you see how quickly Karen put on her jacket? She’s really speedy today.” Other children take notice of this kind of recognition and improve their behavior.

It’s very important for parents to help older children recognize the importance of their role as teachers-by-example, and not allow them to grab toys from the baby or treat him roughly whether he objects or not.

A third important teaching method is to observe where the child is in understanding and interest, and then to present opportunities to utilize his capabilities and interests to lead him to further understanding. For example, as Eric crawled about exploring objects, he would pick them up, study them, then give them a little toss, flipping them over in the process. We observed that he was probably learning something about the weight, composition, and motion of objects in this way, and so we chose toys from the Acorn toy library which responded to this type of action such as rattle balls and blocks. He showed sustained interest in rattle balls because they responded so well to his unique method of exploration. As he plays, we can tell him that this rattle ball is red and this one is yellow, and say, “See it roll,” and “Hear the sound it makes.” When he’s satisfied with what he’s learned from this method, he’ll go on to other discoveries and methods.

As we observe, we see that Julia can match colors but doesn’t name them yet. We name the colors for her as she matches; then one day we ask for a red one or a green one and she gives it to us. Soon she’s telling us the colors.

Craig repeatedly pointed to letters in books and looked up questioningly. We named the letters or words that were so interesting to him, and though we made no effort to “teach” him, he was reading very shortly after learning to talk.

Learning takes place quickly and naturally when it follows the child’s leading rather than being imposed upon him. It also helps to see what the next steps in learning are and to present challenges that the child will meet successfully. As he builds success upon success, he gains confidence in his ability and continues trying.

Rather than presenting a one-year-old at first with a complicated shape-sorter such as the Tupper Rattle Ball, we start with sequential shape-sorters that just have a round hole, go on to the ones with a round and square hole, and later add the others. Also, a way of simplifying a complex shape-sorter is to turn it to fit the shape the child is holding.

With all this interest in the child and what he is doing, we need to remember another important method, and that is training – holding the child to right action. We thus help the child see that he can do what is expected. We not only need to see Jimmy as obedient, helpful, cooperative, courteous and selfless, and expect him to be so, but we must make sure that his actions demonstrate these qualities.

If he resists or ignores loving, positive, expectant requests, this may mean picking him up and helping him do what he is asked; or, it may mean having him sit on a chair or in his room for a few minutes to do some good thinking. If we are loving, yet firm and consistent in expecting right behavior when the child is young, he will form habits which lead to self-discipline and dependability as he grows older.

We parents learn so much along with our children, and the more we know, the more we see there is to learn. We shouldn’t be discouraged when challenges present themselves. In helping children learn, we sometimes seem to come to little hurdles (or big ones). Coming to a hurdle doesn’t mean we are failing as parents, but that we need to find the way to help the child jump over it. And, what a joy it is when we remember that we’re not “stuffing sausage” but looking to find pearls.

Directions

Directions